Conservationist Spring 2025

From the President

DuPage forest preserves are coming to life with wild blooms from bloodroot to Virginia bluebells. The trees are starting to show their new leaves, and everything feels fresh and full of promise. This new growth not only gives forest preserve visitors a burst of color but also provides vital resources for some of our ecosystems’ smallest inhabitants. You can read about a few of them in this issue’s two feature articles below.

You can help efforts to support these busy workers by adding native flowers to your own backyard. To make upcoming gardening projects easier, the Forest Preserve District is again hosting a two-day Native Plant Sale, this year on May 16 and 17, and is offering native landscaping programs as part of its spring calendar lineup.

With the warmer weather, I recently spent time biking along some of the forest preserves’ 175 miles of scenic trails. It made me think of how proud I am as a county resident that officers from our Law Enforcement department are taking the initiative to lead a multiagency bike safety and education campaign. The goal is to promote responsible riding and ensure public safety not only on DuPage trails but also along those in adjacent counties. The effort will also cover a range of safety topics, including speed limits, yielding to other trail users, and understanding e-bike classifications and regulations. You can read more about it by following us on social media throughout May.

Spring is such a wonderful time to enjoy the outdoors, whether on foot or by bike. I hope you get to experience the beauty of the forest preserves soon!

Daniel Hebreard

President, Forest Preserve District of DuPage County

News & Notes

Our Awesome Volunteers

In recognition of National Volunteer Week, April 20 – 26, the Forest Preserve District applauds its 737 long-term volunteers, 250 one-time natural resources volunteers, and 95 volunteer groups. Last year, these dedicated individuals donated more than 58,500 hours with an in-kind value of nearly $2 million!

With a variety of one-time, seasonal, and yearlong opportunities across 12 programs, the District is sure to have something to fit your schedule, pique your interest, and ignite your passion. For details visit our Volunteer page or contact us at 630-933-7233 or volunteer@dupageforest.org.

District Earns S&P AAA Rating Once Again

The Forest Preserve District has earned a AAA rating from S&P Global Ratings for its series 2025 general obligation limited-tax bonds, ensuring funding for certified master plan projects without raising debt-servicing costs or increasing taxes.

S&P also affirmed its AAA rating on the District’s existing general obligation debt — the highest rating assigned by the credit-rating agency. The District has maintained this top-tier rating since 1997, consistently demonstrating strong financial stewardship and leadership.

The rating reflects several key factors, including the District’s outstanding financial management practices and the strength of DuPage County’s diverse and thriving economy. The recent passage of a voter-supported referendum to increase the District’s operational levy also underscores continued public trust and investment in natural resource preservation.

The S&P report cited the District’s proactive leadership, healthy reserves, operational flexibility, and substantial landfill fund resources as key factors in maintaining its strong credit profile.

For more information, including the full ratings report, visit the Forest Preserve District’s Budgets and Financial Reports page.

Collections Corner

Imagine the soundscape of a forest of chutes and quick-moving belts. The cranking of gears, the whisper of grain sliding across wood, the slow beat of rotating pulleys. These were the sounds of Graue Mill when bucket elevators, such as the one shown to the right, moved grain throughout the building.

When a farmer brought product to the mill, the miller would weigh it and pour it through a chute in the floor, where it would collect in a bin. Buckets attached to a belt or chain driven by a pulley system would scoop up the grain and carry it to the upper levels of the mill, where it spilled into wooden chutes. These chutes directed the grain into grinding millstones, kicking off the first step in the flour-making process.

Although similar technologies existed even in Roman times, they were only applied to gristmills in the late 18th century by a man named Oliver Evans. It took several years to find a way to make his design of an automatic gristmill work smoothly, but in 1790 he applied for a patent, which George Washington signed and approved on Dec. 18 that same year. The automated gristmill became extraordinarily popular across the United States throughout the 19th century.

Aside from this mechanism, other remnants of the milling system remain at Graue Mill, including square-shaped holes in the ceiling, which were boarded up when the mill transitioned from factory to museum.

You can see these interesting aspects of the mill this season from April 16 through Nov. 16, when the mill will be open Wednesday – Sunday 10 a.m. – 4 p.m. and closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. For details and upcoming programs, visit our

Graue Mill and Museum page.

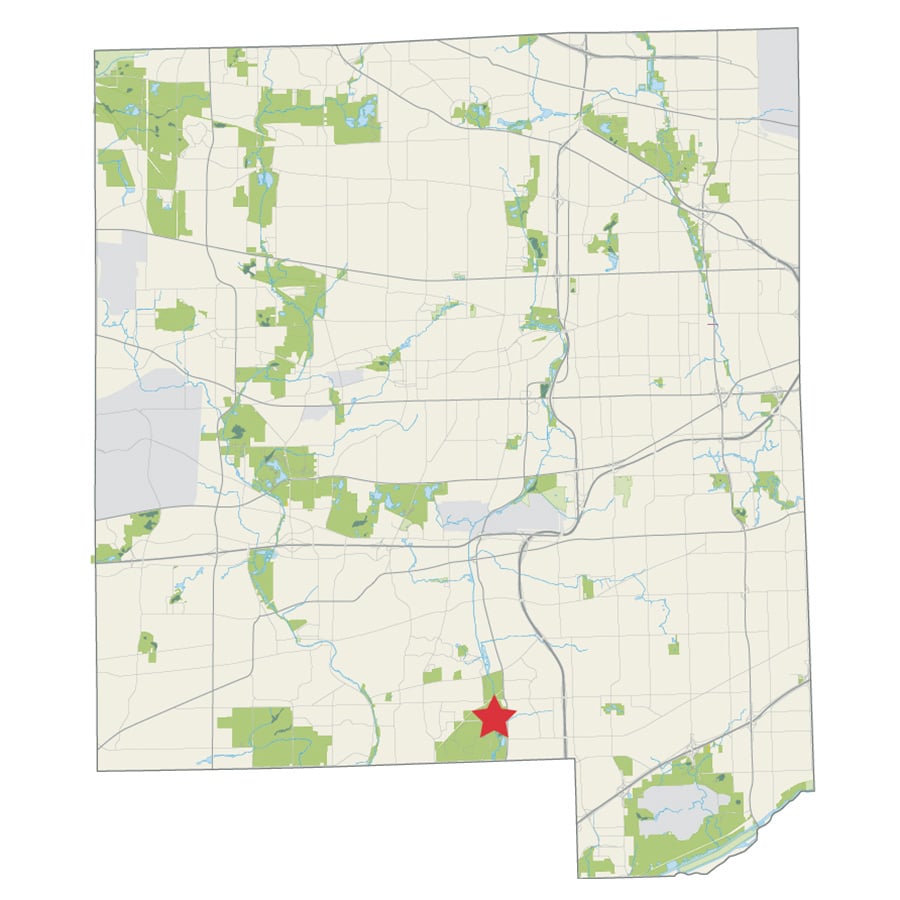

35 Acres Added to Danada

In November the Forest Preserve District finalized the purchase of 35 acres on the east side of Danada Forest Preserve in Wheaton, expanding a critical corridor to nearly 2,500 acres of protected open space in one of the county’s most developed areas.

The $12 million purchase includes 33.3 acres of open space, 1.7 acres of 100-year floodplain, and 0.8 acre of wetlands. It’s bordered on three sides by Danada and The Morton Arboretum, creating vital wildlife corridors that allow animals to move freely and find food, shelter, and mates. These connections also enhance ecosystem health, improve biodiversity, and provide scenic green spaces for residents to enjoy.

Parson’s Grove, located in the southeast corner of Danada, showcases native wildflowers each spring, including wild geraniums, trout lilies, and trilliums. The new property will help protect this rich ecosystem and expand opportunities for residents to experience nature.

District Wins Multiple Ribbons at IPRA Conference

The Forest Preserve District took home multiple awards at January’s Illinois Park and Recreation Association Conference, the largest state conference of its kind in the nation.

The District took first place for its “Preserved for You” social media campaign, its dupageforest.org website, and the long-form video Mussel Matters, a documentary created in partnership with The Conservation Foundation and North Central College. It took second place in large-format marketing for the design of its ranger adventure trailer (shown above), third place in short-form video for “Life Cycle of a 17-Year Cicada,” and third place in agency showcase for its tabletop display.

You can see many of its award-winning shorts on YouTube and by joining us on Facebook and Instagram.

Greene Valley to Benefit from Illinois Grants

The state of Illinois has awarded the Forest Preserve District a $600,000 Open Space Land Acquisition and Development grant to fund significant improvements at Greene Valley Forest Preserve in Naperville.

Gov. JB Pritzker and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources announced the grant in December. It was part of a statewide initiative supporting 100 local parks projects.

Established in 1986 by the Illinois General Assembly, OSLAD is a cost-sharing program that helps communities acquire and develop land for parks and outdoor recreation. One of Illinois’ most popular grant programs, OSLAD has provided $640 million in funding since its inception.

The OSLAD grant will help fund several key projects outlined in the Greene Valley master plan, which the Forest Preserve District adopted in April 2023. These projects include relocating the entrance drive, enhancing picnic shelters, adding a canoe and kayak launch, installing flush restrooms to replace latrines, and realigning trails. A highlight will be a new patio near the historic Greene Barn, which will provide an enhanced visitor experience at the historic site.

Thank You for Being a Friend

The Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County gratefully acknowledges those who donated $500 or more during the fourth quarter of 2024 and others whose cumulative gifts through monthly giving exceeded $500 for the year. The Friends engages the community in philanthropy to advance the District’s mission and master plan for the benefit of wildlife and wild areas and to increase sustainability in the forest preserves.

Learn more or donate at online or mail your gift to the Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County at 3S580 Naperville Road in Wheaton, 60189. To discuss your giving plans or learn about Friends’ board service opportunities, please contact Partnership & Philanthropy at 630-871-6400 or fundraising@dupageforest.org.

Gift of $1 Million or More

Estate of Charles Johnson

Gift of $50,000 – $99,000

International

Gift of $20,000 – $49,000

G. Carl Ball Family Foundation

Gift of $10,000 – $19,000

Ecolab Foundation

Fidelity Charitable

Larry C. Larson

Gift of $2,500 – $9,999

Anonymous — 2

Mary and Harold Bamford III

Elaine Novak Jans

Faith Lambrecht

Bob and Diane Miller

Ranch Spur Charitable Trust

Patricia Reilley and Michael Davis

Schwab Charitable

Michael and Diane Webb

Jerry and Jody Zamirowski

Gift of $1,000 – $2,499

Anonymous

Diane and Joe Addante

Lois Barnett

Roman and Molly Boed

Corryn Greenwood

Judith Grey

Joel Herning

Susan Johansen

Mary Lotz

Carol McGee

Seth Becker and Helen Nam

Susan A. Page

David and Eileen Stang

Terri Tarka

Steven and Gayle Tyriver

Margaret Votava

Wickenkamp Family Fund

Gift of $500 – $999

Anonymous — 2

Coral Baran

Robert and Marcy Cap

Chicago Ornithological Society

Judy and George Fitchett

Jeff and Bonnie Gahris

H. Susan Jones Charitable Fund of DuPage Foundation

The Kannegiesser Family

John Manley

Guy and Sharon Matthew

Rebecca McDade

The Provenzale Family

John Schofield

John and Maria Shalanko

Steven and Megan Shebik

Ann Storm

The Shimkus Family

Morgan Stanley

Steven Szafranski

John and Marion Tableriou

Jerry and Amy Tavolino

Diane Telander

Charles and Sandra Youngstrom

Robert Watt

Hans and Lisa Weckerle

Thomas Williams and Kelly Quinn

Ant Candy

Ants forage the seed of a bloodroot plant. Image © Alex Wild

This time of year, some of the earliest plants to emerge and bloom in DuPage woodlands are spring “ephemerals,” showy but short-lived flowers that often die back by the time the trees above fully leaf out. By summer, some ephemerals will have completely disappeared from the landscape but not before producing seeds to ensure new plants sprout over the coming years. A host of seeds scatter via wind or water, but some spring wildflowers depend on a special dispersal method: ants.

Wildflowers that rely on ants produce seeds with oily appendages called “elaiosomes,” which are rich in fats, protein, and carbohydrates. Elaiosomes come in different shapes and colors, but they all produce oleic acid, an important pheromone ants are quite familiar with.

When an ant dies inside a colony and starts to rot, it begins to emit oleic acid. The acid serves as a chemical attractant, drawing in live ants and triggering them to carry the dead ant out of the nest. When a seed’s elaiosome is fully developed, ants sense the oleic acid and seek out the ripe seed. In this case, though, the ants carry the seed into the colony, where they strip away the nutritious elaiosome to feed to their growing larvae, leaving the hard, inedible seed untouched and in an ideal growing space.

Woodland ant nests are often in damp environments such as soil or spongy, decaying wood, and each has a waste chamber called a “midden.” This moist, nutrient-rich chamber provides ideal conditions for germination. It’s also a protected space. Once a seed is buried within, it’s unavailable to seed-eating wildlife living above ground. The new plant can grow until it breaks through the soil surface the following spring.

This ant-assisted seed dispersal is known as “myrmecochory” and is an example of mutualism, a relationship where two organisms benefit from each other. In this case, the ant gets a nutritious meal — and an early one. Since spring wildflowers bloom before most other native plants, they also produce seeds relatively early in the season at a time when other seeds and sources of food for wildlife are still scarce.

The seed gets not only a rich, protected environment but also a place to grow away from the competition. Woodland ants may only carry a seed 6 feet from where it dropped — a seemingly short distance within an expansive forest — but that’s enough space for a new plant to avoid having to share resources with its predecessor.

An ant carries the seed of a bloodroot to its nest. Image © Bill Duncan

Image © Brian Gratwicke

To be fair, ants are likely not the only insects elaiosomes attract. Some research has documented yellowjacket wasps foraging for and carrying away seeds with elaiosomes. From a plant’s perspective, attracting a greater diversity of insects to help disperse seeds is beneficial. Flying insects especially can transport seeds farther away from the source plant, potentially allowing plants to mix genes or colonize new habitats.

But this doesn’t explain why some spring wildflowers grow across so many regions. For example, since the last glacier receded about 10,000 years ago, wild ginger has spread over a thousand miles across eastern North America, from Canada through states along the Gulf of Mexico. If it relied solely on ants and flying insects, wild ginger likely could not have spread so far. Some scientists believe white-tailed deer and other mammals may have helped. Deer in particular love munching on tender spring plants, unintentionally consuming the seeds and then excreting them as they travel.

Still, an estimated 11,000 plant species worldwide depend on ants. A few of them grow here in DuPage. Common woodland spring ephemerals in the forest preserves that produce elaiosomes include bloodroot, wild ginger, red trillium, celandine poppy, and Dutchman’s breeches.

This form of seed dispersal highlights the role ants play in the ecosystem and their effect on woodlands. For example, wild ginger is a host plant for the pipevine swallowtail butterfly. (This means the butterfly’s caterpillars eat wild ginger as they grow.) Dutchman’s breeches provide pollen to bumblebees, and mammals such as white-tailed deer and eastern cottontails eat the supple shoots of red trillium. All of these relationships along the food web exist thanks to ants.

Ants are often unseen and may not be as charismatic as bees or butterflies, but it’s still worth taking time to appreciate their handiwork as you hike a forest preserve woodland trail this spring. Their ability to help create a spring tapestry of wildflowers and maintain a healthy forest cannot be denied. After all, ensuring an abundant and diverse wildflower population has benefits beyond pretty views.

An ant moves a seed that, if conditions are right, will grow into a celandine poppy. Image © Bill Duncan

Image © wetlandfan

Dutchman’s breeches would not bob over the floors of DuPage forest preserve woodlands without ants to spread their seeds. Image © Martha Rosetta

Image © Bill Duncan

Our Wonderful (and Rare) Bumblebees

A rare rusty-patched bumblebee feeds on native joe pye weed. Image © John Zakelj

As plants and animals wake up from their deep winter slumbers, one familiar and fuzzy insect is part of that revival: the bumblebee. Out of the 12 types of bumblebees in Illinois, 10 live in DuPage forest preserves. These insects, which belong to the genus Bombus, have significant ecological value because along with other bees as well as beetles and flies, they’re pollinators.

Bumblebees have keen eyesight and can sense odors via their antennae, adaptations that help them find pollen- and nectar-laden blossoms. After latching onto a flower’s anther (the part that contains pollen) with its mouthparts (called mandibles), a bumblebee performs what’s called “buzz pollination.” It vibrates strong muscles in the middle of its body to shake the pollen off the flower. The fallen pollen clings to the bee’s sticky, electrically charged hairs. As the insect grooms itself, it moves the pollen into baskets called “corbicula” on its hind legs.

As the bee continues to forage, it carries pollen from flower to flower, performing the cross-pollination needed for flowers, shrubs, and trees to reproduce.

This time of year, most active bumblebees are likely queens emerging from hibernation, searching for nectar, pollen, and a new nest site to start growing their colonies. A queen flying low to the ground in a zigzag pattern is probably scouting for abandoned rodent holes or similar safe havens to nest in. Other bumblebee nests may be created under leaf litter, logs, or bunched grasses or in any preexisting hole that has protective and temperature-controlling insulation.

Once an adequate nest site has been found, the queen has the delicate and important job of developing the next generation of bumblebees as well as the next queen. She starts by using wax from her abdomen to build cups, which she’ll fill with nectar to sustain her as she begins laying eggs. The first round of eggs rest in fused bunches of pollen, called a “brood clump.” During this period, the queen is constantly foraging for food for herself, guarding her nest, and maintaining the nest’s internal temperature. She warms the nest by vibrating her muscles and cools it by thrumming her wings.

A bumblebee’s staticky hairs help the insect collect pollen. Image © Wellcome Images/Science Source

Female worker bumblebees tend to their colony’s nest. Image Emvats/stock.adobe.com

As the weeks progress, the eggs develop into larvae and eventually into adult female workers, who can now be the ones to forage and guard the nest while the queen continues to lay eggs. Some females will be reared to be new queens, who will leave the nest to mate. Not until late summer will the original queen start to lay unfertilized eggs, which then become drones, or male bumblebees. By the end of the season, a colony can have between 30 and 400 bees, but only the new queens will live on to hibernate and start the process over again next spring.

DuPage County’s lineup of these fuzzy pollinators is special because it includes the nation’s only federally endangered species, the rusty-patched bumblebee. You can identify it by looking on the second abdominal segment for a patch of rusty brown hairs that almost covers the entire segment. The rest of the segment is yellow.

The rusty-patched bumblebee historically covered the eastern United States, the upper Midwest, and southern Canada, but since 2007 its range has dwindled. Although there’s no definitive cause for the decline, researchers theorize that habitat loss, pathogens, pesticides, competition with nonnative and managed bees, and the effects of climate change are all contributing stressors.

This bumblebee has been observed in a variety of habitats from woodlands, prairies, and agricultural fields to parks and gardens, the common thread being a site with sufficient nectar and pollen from varied and abundant flowers that bloom from spring to fall near an area suitable for nesting.

Thankfully, there’s much we can do to help this vulnerable bumblebee that calls our county home. First, pass on the use of pesticides, which can harm beneficial insect pollinators as well as whatever you’re trying to target. Second, landscape with plants that provide enticing food and habitat. According to one study, rusty-patched bumblebees favor several native flowers. Early bloomers such as Dutchman’s breeches, spring beauties, shooting star, Virginia waterleaf, and wood betony sustain queen bees emerging from hibernation in early spring. Summer bloomers include St. John’s wort, monarda, Culver’s root, mountain mint, and spotted joe pye weed. As fall approaches, native field thistle, obedient plant, turtlehead, showy goldenrod, and New England aster provide nutrients until it’s time for the new queens to hibernate. Many of these plants will be available at the Forest Preserve District’s spring Native Plant Sale on May 16 and 17.

If you think you see a rusty-patched bumblebee, do not try to handle it. Bumblebees are nonaggressive, but they can sting if provoked. The main point, though, is to not disturb them. Instead, take clear, close-up photos, and report the sighting at the University of Illinois' BeeSpotter website or at iNaturalist. The University of Minnesota in particular has an iNaturalist project called Queen Quest, where anyone can upload pictures of queen bumblebees in early spring so ecologists can identify them for research purposes. It’s a fun way to contribute to conservation!

Bumblebees are some of the planet’s most important pollinators, so if you find a hibernating queen or nest, please leave it be. After all, that queen has a lot of work to do in the season ahead!