Conservationist Spring 2023

From the President

As I write this, I’m hearing cardinals and robins calling outside the window, and I can’t believe we’re welcoming yet another spring in the forest preserves.

As I write this, I’m hearing cardinals and robins calling outside the window, and I can’t believe we’re welcoming yet another spring in the forest preserves.

The past winter has been busy for us as we plan for the upcoming spring and summer. The first phase of construction at Willowbrook Wildlife Center is well underway, and we’re preparing to move our resident animals to their new and improved habitats. The exterior renovations at the historic Mayslake Hall are absolutely amazing and will be completed later this year. We continue to work on the various restoration projects throughout the county, removing invasive species and restoring our preserves to their original natural state.

In this edition of the Conservationist we’re also featuring aspects of the forest preserves you might not otherwise notice. For instance, did you know that small complex (and sometimes colorful) ecosystems are living right below your feet? Or that our ecologists are providing the county’s bass, bluegill, and northern pike with underwater structures that create not only attractive habitats but also great fishing? You certainly will after reading this issue! Plus you can browse through our spring calendar. (Make sure to check out our dates for this year’s native plant sale so you can grow a piece of the preserves in your own backyard.)

Things are beginning to blossom and green. Let’s breathe deep and experience the best of it in our DuPage forest preserves!

Daniel Hebreard

President, Forest Preserve District of DuPage County

News & Notes

Collections Corner

With the arrival of spring, in addition to the grasses and flowers popping up in the preserves, we’re seeing the plants that make up sources of food beginning to grow.

In the 1890s, most of the county and the country was rural and integrally connected with food production. Kline Creek Farm, the Forest Preserve District’s 1890s living history farm, displays several artifacts used at that time.

Some are not only displayed but also put to work. The farm’s 13-row Oliver grain drill is one of them. This 8-foot-wide planter hitches to a team of draft horses, enabling the farmer to plant 13 rows of oats, buckwheat, and other grains. Using three hoppers, the Oliver grain drill can also plant a row of crops, plant a cover crop to protect the soil, and fertilize in one pass.

This spring, join one of the farm’s Spring Planting on the Farm tours to learn how families worked to get spring plantings done and what went into planning the kitchen garden. You might also get to see the farmers work in the fields and gardens planting the year’s crops.

News From Willowbrook Wildlife Center

Willowbrook Wildlife Center is getting ready to start construction on its new treatment and visitor center. The building, which will open in 2024, will showcase the behind-the-scenes medical and rehabilitation process. Visitors will be able to view animals as they’re examined, treated, in surgery, being fed, and rehabilitated through windows and video monitors.

During this time, the current visitor center will remain closed as will access to the trails from Park Boulevard. Animal admissions, though, will remain open 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. seven days a week.

Willowbrook treats an average of 10,000 sick, injured, and orphaned animals each year.

On another note, the center is moving the animals on the outdoor exhibit trail to their new homes behind the scenes, where they will still get daily, high-quality care but in a less stressful environment. To keep up to date on all the latest, follow the center on Facebook @willowbrookwildlifecenter.

Mayslake Update

Restoration continues this spring on the 100-year-old Mayslake Hall, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. Masons are rebuilding the parapet walls (the extension of the walls that meets the roof), and roofers are repairing the slate shingles. The final step will be to replace some of the missing windows and doors. The Forest Preserve District expects the hall to be fully reopened by the end of July and is already planning new exhibits and programs.

Thank You for Being a Friend

The Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County is a 501(c)(3) organization engaging the community in philanthropy to advance the vision of the Forest Preserve District. We are grateful to recognize gifts of $500 or more made October through December 2022 and monthly donors whose combined contributions exceeded $500 in 2022.

To donate, visit dupageforest.org/friends, or mail a check made payable to the Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County to 3S580 Naperville Road in Wheaton, IL 60189. If you have questions, contact Partnership & Philanthropy at 630-871-6400 or friends@dupageforest.org.

Gift of $20,000 or More

Navistar, Inc.

Gifts of $10,000 – $19,999

G. Carl Ball Family Foundation

Ellen Alekno Wier

Gifts of $2,500 – $9,999

Anonymous

Mary and Harold Bamford III

Patricia Reilly Davis

DuPage Birding Club

Ecolab Foundation

Elaine Novak Jans

Larry Larson

Elaine Libovicz

Mary J. Demmon Private Foundation

Nicor Gas

Michael and Diane Webb

Wheaton Bank and Trust

Gifts of $1,000 – $2,499

Anonymous (2)

Seth Becker and Helen Nam

James and Valerie Carroll

DocuSign

Domtar

Michael Foral

Corryn Greenwood

Paul H. Herbert

Joel Herning

Carol Hughes

Mary Ann Mahoney

Carol McGee

Monica Sentoff Charitable Fund

in Memory of Stephen H. Sentoff

Donald and Susan Panozzo

Farrah Qazi in Memory of Nadia Qazi

Diane Telander

Bonnie Walk

Robert Watt in Memory of Ellen

Gifts of $500 – $999

Anonymous (2)

Diane and Joe Addante

Benjamin Adler

Coral Baran in Memory of

Robert Baran

Brian and Dana Battle

Chicago Ornithological Society

Cheryl Clark

Jonathan Dean

Downers Grove Junior Women’s Club

in Memory of Robbie Pfister

Lorena Fogg

Howard Goldstein and

Margaret McGrath

Judith Grey

Tracy and Keith Hernandez in Honor

of Amelia, Jake, and Ryan

Frances Holbrook

Susan Johansen

Joliet Catholic Academy Wildlife Club

Tim Letizia

Mary Lotz

Guy and Sharon Matthew in Honor of

Michael Matthew Memorial Fund

Natural Communities, LLC

Carol O’Neal in Memory of

Julie Julia Jules

Bernard and Karen Rudnik

Saint Gobain

Adam and Melissa Schmitz

John Schofield

Tom Schutz

Ann Storm

Steven Szafranski

John and Marion Tableriou in

Memory of Alexis Breeze and

Colby Jebidiah

Frank and Patricia Troost in Memory

of Barbara Simons

Doug Zimmer

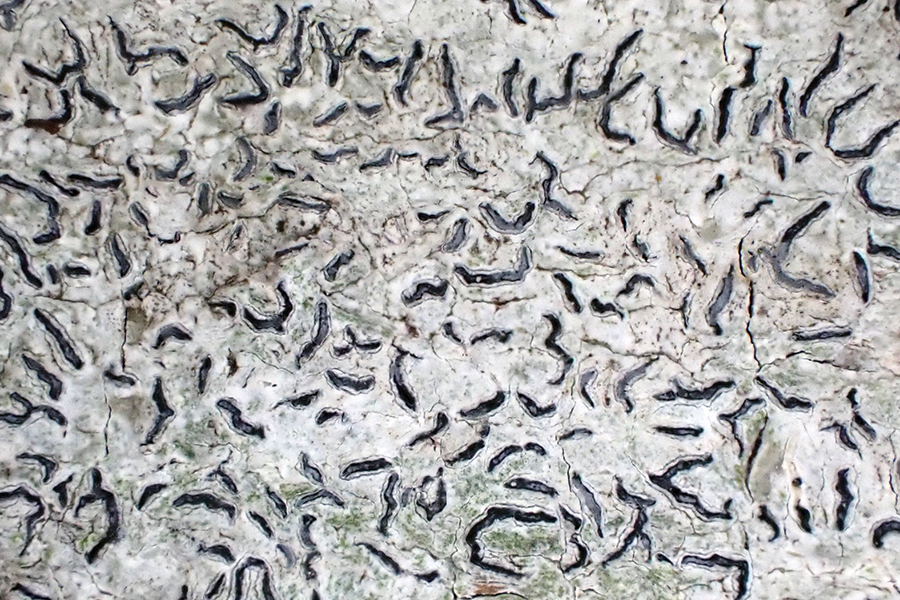

Liking DuPage Lichens

In DuPage backyards, woodlands, and forest preserves a concentrated community of archaic organisms clings to rocks, trees, and buildings. They’re not quite plants, and they’re not quite moss, and they have names like British soldier, pixie cup, lipstick powderhorn, trumpet, and candleflame. They’re lichens, and each is a unique ecosystem.

A lichen is a two-part organism composed of an alga and a fungus. (One third of all of Earth’s fungi exists as a part of a lichen.) It’s a symbiotic relationship, meaning both parts benefit. The fungi provide much-needed structure as well as water, which they absorb from the air, and the algae provide energy via photosynthesis, which converts sunlight into carbohydrates and vitamins. The algae also give lichens their color. Reproduction mostly happens vegetatively, which means a part of a lichen will break off and start to grow elsewhere.

Some lichens, like common script lichen, grow thin and crusty. Others, such as candleflames, resemble wavy leaves. Certain species look like fine hairs, and some look like miniature trees, such as British soldier and trumpet lichens.

Fossilized lichens date back 400 million years with evidence that suggests they may have existed as far back as 600 million years. Today, over 3,600 species live on the planet covering about 7% of the surface. Together, these algae-fungi organisms live in places where independently they would not otherwise survive. For instance, an estimated 250 types of lichens grow in Antarctica, where only two species of flowering plants exist, and many survive in the desert, going dormant during periods of drought. (This latter fact is one reason to stay on the trail while exploring the outdoors. You might accidentally break off brittle, delicate lichens that are merely slowing their growth through difficult conditions.)

Lichens grow slowly, so the substrates they grow on need to be stationary or stagnant, such as rocks, soils, tree bark, and forgotten structures like old farm equipment. Lichens often grow on older or dead trees because the trees’ growth rate has slowed, making the bark more stable than on younger trees. If a lot of lichens are growing on a younger tree, it may mean the tree is suffering from bound roots or some other complication. (Lichens do not harm trees on which they live.)

British soldier (Cladonia cristatella)

Candleflame lichen (Candelaria concolor)

Common script lichen (Graphis scripta)

So why are lichens important? For starters, they’re a building block for other growing organisms. As they break down, they form a thin layer of soil that larger lichens, mosses, and plants can take root in.

They also benefit local wildlife. Some birds, such as the ruby-throated hummingbird, use lichens for nesting materials. The lichens not only provide insulation but also help the nests blend in with their surroundings. Some insects have adapted to look like lichens for camouflage, and many insects use lichens for shelter.

Historically, humans have used lichens as a source of food, medicines, and dyes, but today we use them for much more. Many lichens are intolerant of high levels of sulfur, heavy metals, and nitrogen, which means if you see plentiful amounts of lichens as you walk through the woods, it’s safe to assume you’re in an area with clean air. This means, too, that as people work toward reducing harmful emissions, they’re simultaneously supporting the growth of lichens. In fact, there’s been a noted uptick in lichen populations nationwide since the establishment of the Clean Air Act in the late 1960s.

Lichens also act as air scrubbers. As they take in moisture and air, they absorb particulates and pollutants and store them in their fungal “bodies.” Because lichen grow so slowly over long periods of time, they act as a kind of living record of the historical air quality of a specific site. This is why scientists who monitor air quality regularly sample lichens.

The next time you’re visiting a DuPage preserve, take in the details of the forest around you, including the unassuming lichens clinging to the trees and rocks. Notice their different colors and structures, and relax in knowing that the air around you is likely fresh, clean, and healthy!

Trumpet lichen (Cladonia fimbriata)

Ruby-throated hummingbirds build their nests with lichens, which not only insulate the structures but also provide camouflage.

The World Underwater

Imagine a calm day. You’re sitting lakeside with a fishing pole in hand. The surface ripples slightly from the wind but is mostly undisturbed. It’s a clear open space free of worry. But for the aquatic inhabitants that live just below, nothing could be further from the truth. Fish have a lifelong fight to avoid predation, find food, and reproduce, and the success or failure of their endeavors is often highly influenced by the amount and type of habitat found within their underwater world.

Habitat is roughly defined as the natural environment of an organism. For aquatic wildlife, fish in particular, the word “habitat” is often synonymous with plants, or “weed beds,” rock piles, woody debris, or a combination. These features are often associated with anglers’ perceptions of “good fishing.”

The benefits of habitat, both natural and supplemental, often influence management decisions on lakes and ponds. The Forest Preserve District, for instance, has been augmenting habitat for over 30 years. Within the past 10 years alone, the District has strategically placed over 280 “fish cribs” such as woody debris or PVC pipes in various bodies of water. These structures create protected underwater spaces where communities of fish can grow and thrive, but they also provide areas where anglers can increase their chances of reeling in a great catch.

In most cases the District places weighted fish cribs on the ice. When spring arrives, the structures merely sink to the bottom, where they collect algae and plankton. Small fish feed on these easy meals, and larger fish, the ones anglers are after, hang out to feed on the smaller.

Structure is often placed based on which types of fish are known to live there, how much habitat currently exists, and what the overall management goals are. For example, if the goal is to increase an angler’s success of catching crappie or bluegill, the District places highly branched woody debris in 5 to 8 feet of water near the edges of weed beds. Based on knowledge of feeding and spawning habits, ecologists know these fish will stay near anything that acts as an umbrella, congregating there throughout their different stages of life and increasing the likelihood that anglers who know that these structures will have success.

Largemouth bass often stay near submerged logs and similar structures that protect their vital spawning beds.

In winter, the Forest Preserve District places structures on the ice that turn into fish cribs when they sink in spring.

Largemouth bass will hold to anything that provides an advantage for a meal — logs, concrete blocks, PVC pipes, weed edges, rock piles, etc. Perhaps more importantly, in areas with little structure, these fish will cling to manufactured spawning benches, sometimes called half logs, which not only give them places to lay and protect their eggs but also provide overhead cover from birds of prey.

But you don’t need to look for manufactured fish cribs to find success. Northern pike, for instance, prefer naturally weedy areas. Walleye and perch tend to hold near drop-offs and hard or rocky structures on deeper edges.

Fortunately, it’s easy to find your next favorite fishing spot in a DuPage forest preserve. The Forest Preserve District’s fishing guide features depth maps of 30 lakes and ponds. These maps, called “bathymetric maps,” are basically topographical maps of the lake bed. They show the locations of key drop-offs and also mark where the Forest Preserve District has submerged fish cribs. You can find these maps online or can request a printed copy of the guide through Visitor Services at 630-933-7248. (Remember, though, that you’ll need an Illinois fishing license if you’re 16 or older and fishing forest preserve waters.)

At several preserves you don’t have to fish only from shore. On select days you can rent kayaks, canoes, paddle boats, and rowboats on Silver Lake at Blackwell and kayaks and canoes on Herrick Lake at Herrick Lake. And if you have your own District-approved nongasoline-powered watercraft with a Forest Preserve District permit, you can go out on Silver Lake as well as Deep Quarry Lake at West Branch, Round Meadow Lake at Hidden Lake, and Mallard Lake at Mallard Lake. Details are also at dupageforest.org or through Visitor Services at 630-933-7248.

And for anglers who prefer to drop a line when the sun is at bay and fish are more active, the District offers fishing until 11 p.m. along the shoreline of Deep Quarry Lake at West Branch (no boating after sunset, though).

There’s a whole underwater world in DuPage County’s forest preserves, and the Forest Preserve District will continue to work to create even more inviting habitat for all the native animals that live there.

Fish like crappie take advantage of artificial fish cribs, which provide a buffet of plankton and aquatic insects.

Northern pike often hang out in shallow weeds, where they feed on bluegill, perch, and frogs.