Conservationist Summer 2024

From the President

No matter who I meet along the trails, I’m always excited to talk with them about what they love about DuPage forest preserves. Over the past few years in particular I’ve noticed quite a lot of common sentiments.

Not surprisingly, people enjoy their forest preserves because they offer great opportunities for recreation and leisure, whether hiking through the woods, picnicking in a scenic grove, or fishing along a peaceful lake. Our 26,000 acres provide countless ways to connect with nature that are close to home, and we’ve all heard in the news how important that is. Time in nature is linked to improved physical and mental well-being and can improve memory, attention, creativity, and quality of sleep.

I know it’s important, too, that people feel safe when visiting the preserves. That’s why year-round, the Forest Preserve District’s force of 25 sworn police officers patrol on foot and by bicycle, ATV, and squad car, assisting visitors while enforcing federal, state, and county laws as well as the District’s General Use Regulation Ordinance.

But the forest preserves provide more than safe places where you can get a break from concrete and asphalt. They contribute to cleaner air and water and help with flood control, benefits we can all gain whether we’re frequent visitors or not. Forest preserves hold rainwater, allowing it to slowly soak into roots and seep into soils that filter out chemicals before they can reach waterways or underground aquifers. Plants absorb pollutants like carbon dioxide and particulate matter through tiny openings in their leaves and use them as nutrients or store them in their tissues.

Of course these open spaces — all preserved for you — are vital to native wildlife. It’s a top reason why the Forest Preserve District works throughout the year to improve and maintain the county’s high-quality woodlands, prairies, wetlands, and waterways.

No matter how you enjoy your DuPage forest preserves this summer, I’ll see you there!

Daniel Hebreard

President, Forest Preserve District of DuPage County

News & Notes

Collections Corner

At the heart of every gristmill are the millstones, the two large round slabs of rock used to grind grain. Millstones can be marble, granite, or sandstone, but those at the Graue Mill and Museum are made of a particularly sturdy and porous material called French buhrstone, a sedimentary rock high in silica. French buhrstone was in high demand in 19th century mills because of its durability and alleged ability to grind whiter wheat flour.

At Graue Mill, grain enters a large wooden funnel called a “hopper” and falls through the “eye” of the two stones. As the top stone turns, the grain moves between the two, where it’s sliced and crushed. It’s ground into smaller and smaller bits until it falls out from the edges into a bin.

The stones have a repeating pattern of grooves called “harps,” which slice the bran from the outside of the grain and guide the grist toward the outer edge of the stones. The large grooves are called “furrows”; the smaller, “feathering” or “cracking.” The flat areas in between, called “lands,” crush the rest of the grain into meal. In this photo you can see a millstone dresser working on the harps on one of the stones at Graue Mill.

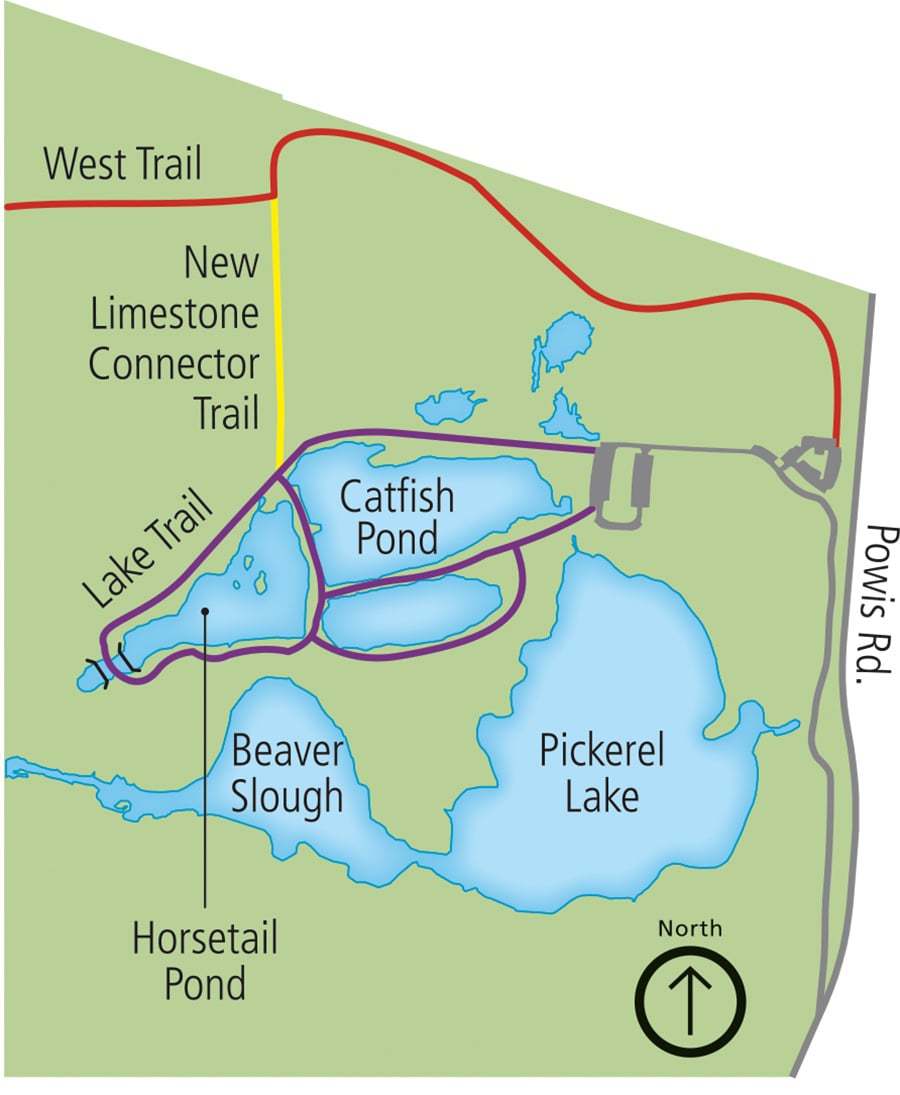

Connector Trail Upgrade at Pratt’s

Work is underway at Pratt’s Wayne Woods to convert the 0.3-mile connector trail between the West and Lake trails from turf to crushed limestone. The project, which received federal Recreational Trails Program grant funding through the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, will be completed this summer.

The trail is north of Catfish and Horsetail ponds and is used extensively by hikers, bikers, horseback riders, and youth-group campers. Access is sometimes restricted, though, during regular turf maintenance or after heavy rains, when horse traffic can create ruts in the wet grass. The 10-foot-wide limestone trail will improve year-round use for all visitors.

Flush Restrooms Coming to Four Preserves

Construction has started on new flush restrooms at Pratt’s Wayne Woods, Mallard Lake, Wood Dale Grove, and Waterfall Glen. The Waterfall Glen building will be near the new parking lot by the Rocky Glen area. The other three will be near existing picnic shelters and will replace pit latrines or portable toilets that were unpopular with visitors.

Construction will include the installation of well water, septic, and electrical systems; a concrete sidewalk (where needed); and a three-stall building kit. At Pratt’s Wayne Woods, crews will also pave some accessible parking space.

The District expects the installations to be complete in October.

The District’s 2019 Master Plan identified flush washrooms as a certified project to improve the level of service for the public and reduce long-term operational costs at preserves that have high visitation numbers and nearby special-use features.

From Crayfish Come Dragonflies

Forest Preserve District ecologists at its Urban Stream Research Center in Blackwell recently released 25 Great Plains mudbugs into the wild. These native crayfish were collected as eggs and reared at the center for the past year as a part of the District’s program to raise federally endangered Hine’s emerald dragonflies.

The crayfish build and live in complex underground burrows with caverns and winding tunnels that can be over 6 feet deep and reach below the water table. The burrows are necessary habitat for Hine’s emerald dragonflies, which, like other dragonflies, spend the first part of their lives underwater as larvae. For reasons ecologists still don’t understand, Hine’s larvae only live in water at the bottoms of burrows created by Great Plains mudbugs.

Paddle Away at Herrick

Weekend visitors to Herrick Lake can now explore the water via one of two paddleboats. Six paddleboats have been available at Silver Lake at Blackwell since 2021.

Rentals for DuPage residents and nonresidents are $20 per hour with a valid government-issued ID and cash or credit card. (Rowboat or one-person kayak rentals are $15 per hour; canoes or two-person kayaks are $18 per hour.)

Rentals are available at Herrick Lake Saturdays and Sundays through Labor Day weekend plus Independence Day and Labor Day 11 a.m. – 6 p.m. At Blackwell you can rent weekends through September and weekdays through Labor Day 11 a.m. – 6 p.m. At both locations, rentals end at 5 p.m.

Visitor Services Saturday Phone Hours

Now through Aug. 24 (except July 6), Visitor Services is available on Saturdays 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. to answer your calls, emails, and online chats. The office won’t be open for in-person visits, but you’ll still get answers to all those questions you missed during the week. Get in touch at 630-933-7248 or permits@dupageforest.org, or use the chat box in the lower right corner of this page.

Thank You for Being a Friend

The Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County is a 501(c)(3) that engages the community in philanthropy to advance the mission and support the purpose of the Forest Preserve District. We are grateful to those who donated $500 or more to the Friends or the Forest Preserve District during the first quarter of 2024.

To learn about opportunities to donate or partner with the Friends, contact Partnership & Philanthropy at 630-871-6400 or fundraising@dupageforest.org, or visit dupageforest.org/friends.

Gift of $25,000 or More

Elaine Libovicz

Gifts of $2,000 – $3,499

Kevin Condon

Edward Jones — Financial Advisor

Mike Dyer

Gifts of $500 – $1,999

Anonymous

ComEd/Exelon

Van Cushing

Claudia and David D’Hooge

Rachel Itano

The Kerschen Family

DJ and Catherine LaChapelle

Mary Ellen and Patrick Mauro

Curtis Nekovar

Michael Ondek

Jefferson and Catherine Reiter

Nancy Rivas

Robert R. McCormick Foundation

Martha and Bruce Sanders

Lisa Savegnago and Ronald Johnson

Marlen V. Schuett

Tyndale House Ministries

Soaring High: Bald Eagles in DuPage County

Just 30 short years ago, a bald eagle was a rare summer sight in the Chicagoland area. Today, bald eagles are soaring in our skies — and are calling DuPage forest preserves home year-round.

On June 20, 1782, the Second Continental Congress approved the Great Seal of the United States, which features a bald eagle. Five years later, the bald eagle became the nation’s official symbol. Based on historical accounts, modern ornithologists estimate that at that time there were upward of 100,000 breeding pairs in today’s contiguous 48 states. Since then, though, bald eagles have faced many pressures.

As a result of habitat loss and illegal hunting in particular, by 1918 bald eagles were no longer found nesting in Illinois. After World War II, the use of DDT, an insecticide favored for controlling mosquitoes and agricultural pests, had a wider, more devastating effect. DDT washed away into local waterways, where it was absorbed by fish. Eagles typically hunt for fish, so the chemical eventually found its way into the birds. The more contaminated fish the eagles ate, the more toxins accumulated in their bodies. In females, this resulted in thin eggshells, which incubating adults easily cracked, meaning fewer hatchlings. By 1963, researchers recorded only 417 breeding pairs in the contiguous 48 states. (Bald eagles are not found in Hawaii, and Alaska has consistently maintained a healthy bald eagle population.)

Early legislation such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940 protected bald eagles from illegal hunting and actions that could harm the birds or their nests. The Endangered Species Act of 1973, which evolved from the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, further benefited bald eagles when they were added to the endangered list in 1978 in most states. But perhaps the most important policy decision was the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s ban of DDT in 1972.

Throughout the later half of the 20th century, many organizations conducted bald eagle reintroduction programs, raising eaglets in captivity to give them a head start before releasing them into the wild, and worked to conserve and protect habitat. Here in DuPage, although not specifically for the sole sake of bald eagles, Forest Preserve District efforts to preserve and create healthy ecosystems have resulted in the return of nesting and hunting bald eagles.

The National Eagle Repository

Eagles are sacred to many Native American tribes. For that reason, since the 1970s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has collected bald and golden eagle feathers as well as any remains from across the country to convey to tribes for religious and cultural ceremonies. If the Forest Preserve District treats an eagle at its wildlife conservation center, it sends any feathers that drop, or any birds that do not survive, to the national repository.

Female and male bald eagles start off mottled brown. They don’t gain their white feathers until they’re 4 or 5 years old.

A bald eagle snags a meal at Herrick Lake Forest Preserve.

Today, both the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (which protects all native birds) and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act continue to make it illegal to disturb a bald eagle nest (including getting too close to one) or to possess any part of an eagle or its nest or eggs. Collectively, actions over the past century have boosted populations nationwide. In 1995 the bald eagle was reclassified as threatened in all contiguous 48 states, and by 2007, when there were 9,789 breeding pairs, it was removed from the endangered species list altogether. In 2019, researchers recorded 71,467 nesting pairs.

Here in DuPage, bald eagles visit several forest preserves year-round. Female bald eagles are larger than males, but plumagewise, they look identical. As juveniles, they’re brown with various degrees of white mottling, depending on their age. Only when they become sexually mature at 4 to 5 years old do they acquire their distinctive white head and tail feathers. In addition to fish, they will eat waterfowl, small mammals, and carrion. Often they can be spotted harassing ospreys in an effort to force the ospreys to drop their prey.

Eagles build large nests in trees near rivers or lakes from November to February. The female lays one to three eggs in February or March, and both parents take turns incubating for about a month. After hatching, the chicks, which are called “eaglets,” stay in the nest for another two to three months.

In winter, Illinois becomes home to an influx of eagles from the north, which gather along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers as well as smaller waterways such as the DuPage and Fox rivers and Salt Creek. Waters in the northern U.S. and Canada completely freeze, so the eagles need to migrate south to find open water and fish.

The recovery of the bald eagle is a great wildlife success story, a result of how governmental conservation agencies, private groups, and individual fans of wildlife can make a remarkable difference. So the next time you’re in a DuPage forest preserve and see a bird overhead with a white head and tail, you’ll know the story.

American or Bald?

In 1766 the bald eagle received its scientific name, Haliaetus leucocephalus, meaning “white-headed sea eagle.” So why do we call them “bald” or “American” eagles? The original common name, “bald eagle,” may likely derive from an older definition of the English word balde, which meant “white” and not “hairless.” “Bald eagle” is recorded as far back as the 1680s, when it was attributed to the bird’s white head. “American eagle” became common in the U.S. after the country adopted the bird as its national symbol.

Gardening for Moths

Don’t get me wrong. I think butterflies are great. But can we take a minute to show a little love for moths? Illinois boasts 150 butterfly species, but the state’s 1,850 species of moths often go unnoticed, likely as most are nocturnal or blend into their surroundings.

Butterflies and moths belong to the insect order Lepidoptera, but they do have some differences, most notably their antennae. Butterflies’ are club-tipped; moths’ are comblike or feathery. Both insects, though, have “scales” on their bodies, which give them color, keep them warm and dry, and improve aerodynamics. Both are also vital pollinators, although recent research suggests moths may be more efficient pollinators than bees or butterflies. Unfortunately, both face the same threats, ranging from degraded or lost habitat, especially in prairies and wetlands, to humans’ use of insecticides. Luckily, the steps we can take to make our yards more friendly for butterflies can help our local moths, too.

Avoiding the use of insecticides is a good place to start, but incorporating certain native plants into a landscape can also benefit Lepidoptera. Like butterflies, moths lay their eggs on plants, and some lay them on “host” plants, ones their larvae (aka caterpillars) prefer to eat. For example, black-eyed Susan and yellow coneflower host wavy-lined emerald moth caterpillars; Clymene moth caterpillars feed on common boneset. Verbena moths lay their eggs on blue and hoary vervains, and snout moths use wild bergamot and spotted beebalm. Virginia creeper hosts numerous types of sphinx moths, and big-leaved and other asters host Isabella tiger moths, whose caterpillars are better known as “woolly bears.” Culver’s root, coneflowers, and goldenrods are associated with species-specific borer moths, and milkweeds are for more than just monarchs. They host milkweed tussock moths as well.

Nectar from native flowers sustains several beneficial adult garden insects, moths included. Moths, such as the clearwing hummingbird moth, that are active during the day feed on species like bergamot and cardinal flower. For the majority that are nocturnal, white or pale-colored flowers that best reflect moonlight — Culver’s root, common boneset, wild hyacinth, white snakeroot, or pale-spiked lobelia among others — make easy-to-find targets.

One of the greatest moth-approved plant additions to a yard, though, is a native tree. One large one can house thousands of caterpillars. Oaks alone host upward of 500 species of Lepidoptera. In the moth world, hummingbird clearwing, cecropia, and large Tolype caterpillars all feed on black cherry and American plum. Polyphemus, luna, and prominent larvae eat hickories and oaks.

Native plants with white or pale flowers can attract moths to your nighttime garden. Common boneset in particular is a vital host plant for Clymene moths.

But homeowners can perhaps help moths the most by limiting the use of outside lighting. Most moths have a strange draw to artificial light, a phenomenon known as “positive phototaxis.” The reason is unclear, but ecologists have a few theories. It may be because these moths naturally navigate with their backs to the brightest light source to orient themselves as they fly. For eons, this source was the sky, a reliable, fixed feature. When encountering an artificial light, this draw causes the moths to fly around it in circles. Other scientists posit positive phototaxis may be caused by certain light frequencies that disorient moths or by ultraviolet light, which may excite females into releasing pheromones, which attract other moths to the source.

Whatever the reason, when moths become entranced by an artificial light, they circle the source until they become weary, unnecessarily expending energy and becoming more susceptible to predators like bats and birds. Homeowners can make things easier for moths by putting porch and garage lights on timers or motion sensors to limit excessive lighting.

In some cases, a moth’s attraction to artificial light can help study moth biodiversity. At Danada, Forest Preserve District researchers aimed a sodium vapor light at a wall to intentionally attract moths. When the moths landed on the wall, the researchers could identify the species, which helped catalog which moths lived in the preserve. At other sites, they experimented with “moth mash,” a sweet, strong-smelling thick paste of banana, brown sugar, and spoiled beer that’s applied to bait stations on trees to attract the insects. With these two techniques alone, the Forest Preserve District has recorded hundreds of different species of moths, information shared on the iNaturalist app to help others better understand northern Illinois’ geographic and seasonal moth distributions.

So this summer, when you work in your yard to attract butterflies, as you begin to see more, know you’re helping our local moths, too. You may not see them directly (most moths are nocturnal after all), but remember that what’s good for one is good for them all!

Milkweed isn’t just for monarchs. Milkweed tussock moths lay their eggs on milkweed, the only plant their caterpillars will eat.