Engineer Devises System to Stop Zebra Mussel Spread

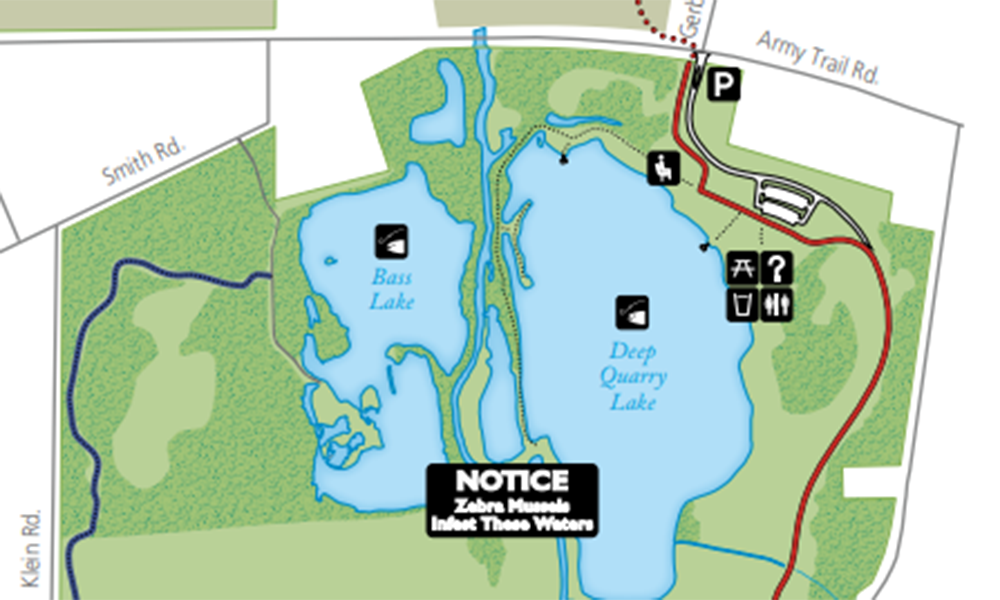

A longtime battle to keep invasive zebra mussels in the West Branch Forest Preserve’s Deep Quarry Lake in Bartlett from spreading to the adjacent West Branch DuPage River took an innovative twist thanks to a method devised by a Forest Preserve District civil engineer.

A pipe had been maintaining Deep Quarry Lake’s elevation, but the District closed it off after discovering zebra mussels in the lake several years ago, District civil engineer Chris Welch said. This caused the lake level to slowly rise and begin washing out the bank separating the lake from the adjacent West Branch DuPage River, he said.

The West Branch DuPage River runs between Deep Quarry and Bass lakes at West Branch Forest Preserve in Bartlett.

“The pipe had to be abandoned to prevent mussels from contaminating the river and threatening all the great restoration work that had been accomplished downstream,” Welch said. “The bank washing out threatened the same contamination, so we had to find some way to either restore the original water elevation or remove the zebra mussel infestation from the lake.”

According to District Natural Resources Director Erik Neidy, “It’s very expensive to physically and chemically treat a body of water with no guarantees that zebra mussels will not return or that they were all removed.”

So Welch researched the matter and found a sand filter system being used in the Ural and Caspian regions of Russia where zebra mussels are native to rivers that serve as the region’s drinking water source. Sand filtration systems were installed along or underneath the river to remove or kill adolescent zebra mussels, Welch said.

“The solution we constructed was basically the reverse of theirs, where the lake water pushes through a sand filter into a pipe, which discharges into a shallow swale and heads for the river,” Welch said.

District crews determine grading while cutting back the shelf for the liner. Clay is also loaded for the project.

In his research, Welch could not find any agencies “this side of the Atlantic” using the sand filter method to control zebra mussels.

Just one adult can filter microscopic plants and animals from 1 quart of water in one day; one colony can clear an entire lake, leaving little food for native animals.

“Our goal is to keep the mussels from entering the river,” said Forest Preserve District Natural Resources Director Erik Neidy. “Even though typically the zebra mussels do not survive in large numbers in moving water systems, we still do not want to be a source for other lakes and ponds downstream that may have a connection to the river.”

This summer trails and streams crews from the Forest Preserve District’s Grounds Department dug an overflow and trap area adjacent to Deep Quarry Lake and installed the sand filter system at the south end of the lake. They also installed piping and sand, which will filter water from the lake before it drains into the West Branch DuPage River, Neidy said.

The liner is installed and preparations are made to install the filter system.

Zebra mussels only reproduce in freshwater when water temps are warm during the spring/summer months. This release of young mussels called “veligers” can be as large as one million per adult female. A large body of water can already have millions of adult females.

As water leaves Deep Quarry Lake, it enters the sand filter and slows the flow, allowing the sand to trap the extremely small veligers between the sand particles while releasing the clean water through a pipe system embedded in gravel under the sand, Neidy said.

“We completed digging the filter in summer 2020,” Neidy said. “To finish the project we need to lower the water level low enough to create a new overflow into the filter at the south end of the lake.

Crews install the filter system that will keep invasive zebra mussels from Deep Quarry Lake from entering the adjacent West Branch DuPage River in Bartlett.

“As the lake levels rise in 2021, the lake will empty into the filter system and trap the zebra mussels and release the clean water,” Neidy said. “We drained some of the lake in 2020 to prepare to create this overflow.”

Neidy said the overflow and sand trap are now operational. The lake’s current level is now the new normal elevation because the system will keep lake levels from getting too high.

Unlike beneficial native freshwater mussels, zebra mussels are so prolific they remove all viable food sources from the water and attach to hard structures, including freshwater mussels. This can forcibly close and starve out good mussels by preventing them from feeding.

Zebra mussels are now in more than 25 states; control costs in the Great Lakes alone is $100-$400 million annually.